Non-executive director shows faith in housebuilder

The first Budget from a Labour Government in 14 years continues to stir heated debate and sceptics readily point to the increase in the yield in the UK’s 10-year gilt to a one-year high to support their case that chancellor Rachel Reeves is on the wrong track. It does not look great that yields are rising in the wake of August’s interest rate cut from the Bank of England, but 10-year government bond yields are rising in France and the US, too, and faster than they are here in the UK relative to local headline interest rates, to perhaps suggest there is a wider issue at work.

FIXED-INCOME FLAP

In principle, the price of benchmark government bonds should rise, and the yield should fall once a central bank cuts interest rates, especially if the monetary authorities give strong hints that further reductions in headline borrowing costs are on the way.

This is because the coupons on existing issue may look more attractive relative to the coupons that will come with newly issued paper, so investors will look to buy the bonds that are already available to lock in higher returns (at least in nominal terms). The price of existing benchmark bonds, such as those with a 10-year maturity, should rise and so the yield should fall, since the coupon payments continue to come at their pre-set level at the pre-set time.

However, the opposite is currently happening. Chancellor Reeves is getting a lot of the blame here in the UK, especially as the 10-year gilt yield is as high as it was during the peak of autumn 2022’s Trussonomics panic.

However, the rate of ascent has been gentler, and the Bank of England base rate now is 4.75%, compared to 2.25% two years ago, so the comparison is not an entirely fair one. French OATs and American treasuries are also defying central banks.

From an investment point of view, the wider uncertainty across sovereign debt markets is a potentially troubling sign, especially as stock markets remain buoyant and investment grade corporate debt markets offer what look like low spreads (premium yields) relative to government issue.

Sovereign fixed-income markets could be worried about inflation, ever-growing budget deficits (and thus ever-growing supply of government bonds) or even the US economy in particular proving more resilient than expected. All three could mean that central bank interest rates remain higher for longer, although for the moment equity markets are sticking to their preferred script of cooling inflation, a soft economic landing (or no more than modest progress) and interest rate cuts. It will be interesting to find out whether equity or bond markets are right, or whether the truth falls somewhere in the middle.

YIELD TO MATHEMATICS

Besides wider macroeconomic concerns, there is a more tangible reason why rising government bond yields could become a challenge for buoyant equity markets, at least in the US, where sentiment feels as bullish as ever.

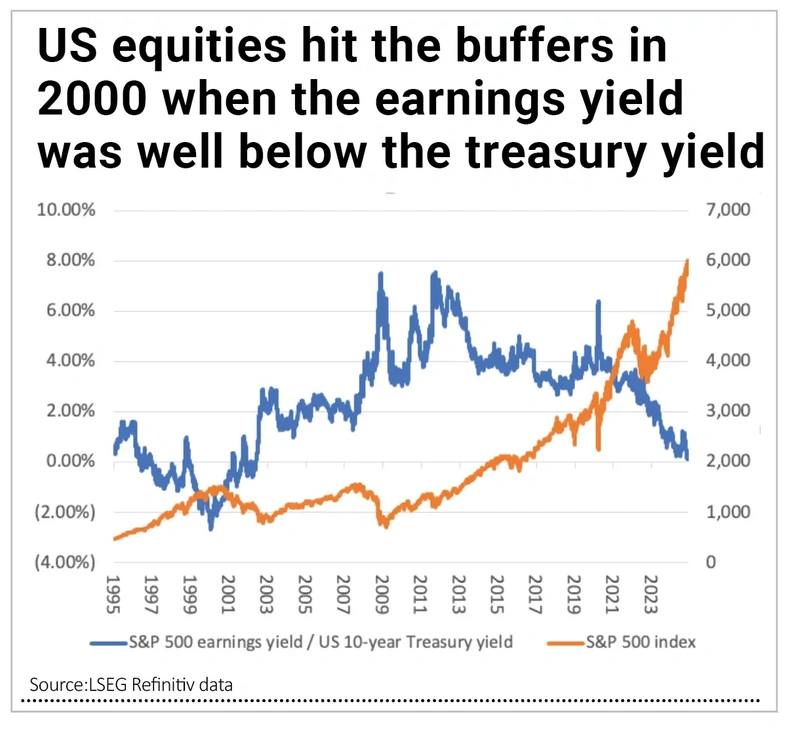

This is because the yield on the 10-year treasury – the so-called ‘risk-free rate’ – is now equal to the earnings yield on the S&P 500.

The earnings yield is simply the inverse of the price to earnings ratio (PE). If the PE is calculated as price divided by earnings to give the valuation multiple, the earnings yield is earnings divided by price with the result expressed as a percentage and, in effect, it measures how much profit a company makes for every dollar (or pound or euro) invested in it.

According to consensus analysts’ estimates, the S&P 500 trades on 22.3 times forward earnings, equivalent to an earnings yield of 4.49%. The ten-year Treasury yield is 4.39%, so investors are being rewarded with just ten basis points of extra return for taking on equity risk.

The premium return from equities is thus at its narrowest point since the early 2000s, when the technology, media and telecoms (TMT) bubble was bursting. Bulls will counter by saying that episode only went pop when the 10-year yield outstripped the equity yield by more than two percentage points – and we are long way from that.

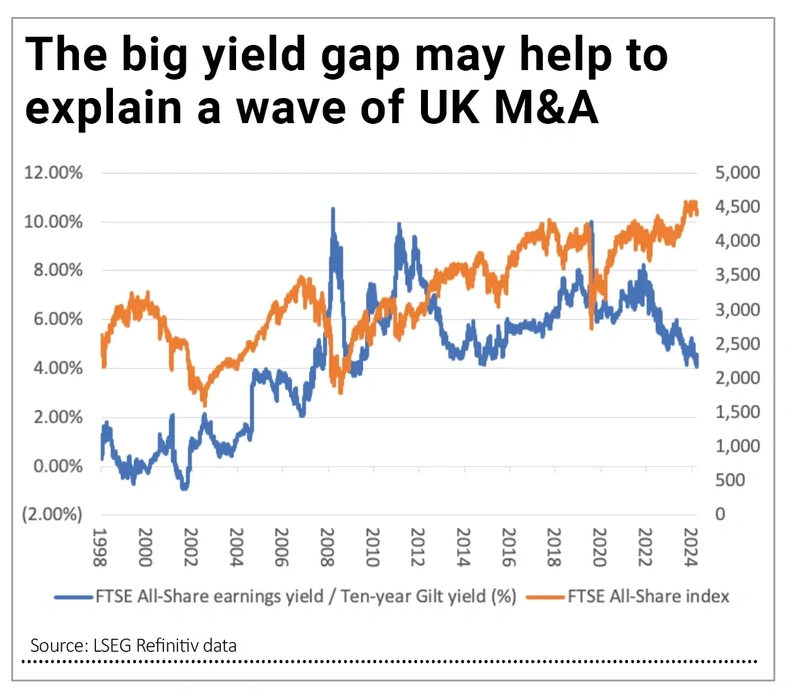

Value-hunters may point to the different picture in the UK. A forward PE of 11 times for the FTSE All-Share equates to an earnings yield of 9%, which beats the 4.5% 10-year gilt yield hands down.

The UK’s own speculative flirtation with the TMT bubble only came to grief when the earnings yield premium over the gilt yield dipped below 2%.

Again, we have some way to go before that point is reached, which is one possible explanation for the ongoing surge in takeover activity in the UK, as private equity and trade buyers snap up UK-listed companies.